top of page

HOW DOES HIP DYSPLASIA EFFECT MOVEMENT IN DOGS?

GRACIE EXLER | 17 JUNE 2025

Hip dysplasia is one of those terms dog owners dread to hear but vets are diagnosing it more often nowadays. Technology which collects data from the dogs movement has allowed us to gather a better understanding of the impact this condition has on dogs and therefore can help aid in the diagnosis.

Hip dysplasia accounts for 30% of orthopaedic (bone) conditions

diagnosed within dogs and is commonly associated with large breeds,

genetically exposed puppies and fast growing dogs.

Hip dysplasia is caused by a change in the forces applied to the coxofemoral joint (hip joint). More specifically the ball and socket joint which connects the femur (thigh bone) to the hip. This starts to reduce the strength of the bone as the cells within bone are not able to produce enough new cells quicker than the old ones getting damaged. This is why hip dysplasia is commonly associated with osteoarthritis (OA).

CLINICAL SIGNS:

- Difficulty standing up or sitting down.

- Narrow based stance.

- Lameness.

- Reluctancy to move.

- Not flexing limbs as high.

- Bunny hopping gait.

- Loading more weight onto the forelimbs.

- Pain/discomfort during range of motion tests.

Dogs are very good at compensating, however, these issues begin to spiral and without intervention will undoubtedly get worse.

Ground reaction forces (GRFs) have become an invaluable part of diagnosis. They provide us with information regarding the amount of force travelling up the dogs limb when the dog land/stands on it. One study compared GRFs in the hindlimb of a healthy dog and a dog with hip dysplasia which found there to be lower GRFs in dog with hip dysplasia thereby indicating that dogs will reduce the amount of weight they load onto the hindlimb. Further research regarding the movement of dogs with hip dysplasia found there to be reduced stride frequency (the amount of strides the dog takes within a second) but a longer stride length. This is said to be due to the joint having more movement (laxity) due to the alteration in forces previously discussed associated with hip dysplasia.

As well as aiding in diagnosis, it can also help determine the best course of treatment for dogs. Non surgical treatment commonly opted for is non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) which helps minimise pain and inflammation as well as weight control for dogs which can be deemed overweight or obese. Conservative treatment has shown to have promising results including that 6 out of 7 owners with dogs diagnosed with hip dysplasia found that conservative treatment helped the dog to return to having a normal gait movement, improved joint range of motion and they were pleased with their dogs activity level.

In more serious cases surgical intervention may be required with the most common surgery being a total hip replacement. This specific surgery involves removing the top part of the femur (femoral head) and replacing it with a metal ball whilst also resurfacing where the ball sits into the socket (acetabulum) with a cup implant allowing for a complete new joint. Dogs which underwent this type of surgery found that range of motion improved in 94% of cases within 5 years after the surgery.

REFERENCES:

Dycus, D.L., Levine, D., Marcellin-Little, D.J., (2017) 'Physical rehabilitation for the management of canine hip dysplasia,' Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 47(4), pp.823.

Farrell, M., Clements, D.N., Mellor, D., Gemmill, T., Clarke, S.P., Arnott, L., Bennet, D., Carmichael, S., (2007) 'Retrospective evaluation of the long-term outcome of non-surgical management of 74 dogs with clinical hip dysplasia, Veterinary Record, 160(5), pp. 506-511.

Fries, C.L., Remedios, A.M., (1995) 'The pathogenesis and diagnosis of canine hip dysplasia: a review', Canadian Veterinary Journal, 36(8).

Miqueleto, N.S.M.L., Rahal, S.C., Agostinho, F.S., Siqueira, E.G.M., Araújo, F.A.P., El-Warrak, A.O., (2013) 'Kinematic analysis in healthy and hip-dysplastic German Shepherd dogs', The Veterinary Journal, 195(2), pp. 210.

Poy, N.S.J., Decamp, C.E., Bennett, R.L., Hauptman, J.G., (2000) 'Additional kinematic variable to describe differences in the trot clinically normal dogs and dogs with hip dysplasia', American Journal of Veterinary Research, 61(8).

Schachner, E.R., Lopez, M.J., (2015) 'Diagnosis, prevention and management of canine hip dysplasia: a review', Veterinary Medication (Auckland), 19(6), pp. 181-192.

WHAT LEADS TO HIP DYSPLASIA:

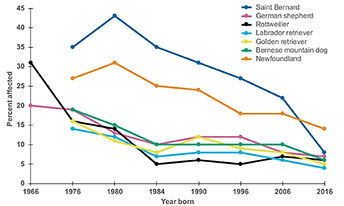

©Hedhammar 2020

Posture difference between a healthy German Shepherd (left) and a dysplastic German shepherd (right).

bottom of page